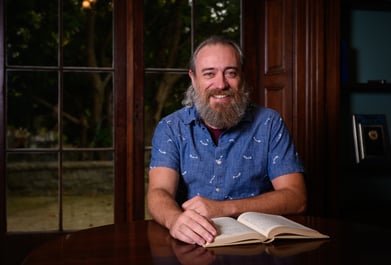

A discussion with Steve Bono, Founder and CEO of Independent Security Evaluators.

One of the great things about working with security experts with different backgrounds and perspectives is that you get to overhear interesting thoughts about the best ways to protect assets. While clearly there are many practices that are “good” or “bad”, the more conceptual aspects of security, like what it means to manage risk, are far more subjective questions that may not have clear answers. On top of that, many ideas that are common today may not represent the best approach, and often these practices were normalized due to reasons that made sense at the time but deserve scrutiny. I sat down with Steve Bono, founder and CEO of Independent Security Evaluators, to discuss one particular area of security management that is critical to success. We talked about topics such as, “who should ultimately be responsible for security? Stakeholders or providers?”

Ben Schmerler: Thanks for taking the time to talk with me, Steve. Before we get into answers and solutions, can you define for me, in your words, the difference between stakeholders and providers?

Steve Bono: Sure. A stakeholder here is someone who places value on data and wants it protected. There can be different kinds of stakeholders. In healthcare, stakeholders can be patients. I care about the protection of my Personally Identifiable Information (PII), so I’m the stakeholder. In another industry, for example, the movie industry, the stakeholders could be the movie studio and others involved in the production.

On the other side are providers. The provider offers some kind of service or product, but doesn’t necessarily suffer from the compromise to the same extent a stakeholder might. Often times who these parties are is obvious, but sometimes there’s a gradient where perhaps it’s a bit less clear.

BS: That makes sense. The reason I wanted to talk to you in the first place about this is that I heard you say that many times stakeholders are not responsible for security, but that they should be, even though in general it’s the providers that are expected to be responsible. What do you mean by that?

SB: I want to be clear. Many providers we work with are great. They care about security, regardless of whether it should or shouldn’t be their responsibility. But what we are looking at now are a series of incentives that don’t benefit the stakeholder, when we rely purely on the provider to implement and manage security. The problem is that providers are incentivized to do the minimal amount of security to meet a specific goal, whether that is a stakeholder goal, a compliance standard, or whatever other checklist needs to be marked off.

BS: That’s sort of a race to the bottom, I suppose. If everything is just the bare minimum, we should probably expect those kinds of results. Do you have any ideas for how we got to this point?

SB: It’s natural for most to think that the provider should be responsible for security. That’s kind of the way we gravitate towards most things in life…it’s easier. We want someone else to do the heavy lifting and we don’t want to pay attention to all of these other things. But the stakeholder isn’t really doing anything to impact change or make things better. If we went back to the healthcare example, most people don’t think their doctor is primarily responsible for their health. While their doctor may treat them or prescribe medicine, the patient realizes generally that they are responsible to engage in healthy behaviors. In fact, the recipient of healthcare often wants to be better. They seek out other opinions, do research, etc. As a matter of fact, for those who have unusual conditions, they often find providers who may not understand it as well as they do. Again, this is why it is important for the stakeholder to have responsibility. They have to advocate for their own interests.

BS: I see. So people don’t really want to do it because it’s hard. I certainly understand that. But is this the sort of thing that is just too hard for the average person who may not understand security?

SB: It doesn’t have to be. The basic information most people need is obtainable and sweeping your security concerns under the rug because you want it to be someone else’s responsibility is ultimately hurting yourself.

One thing we talk about a lot at ISE is “threat modeling”, which is understanding what you are protecting, who is coming after it, and so on[1]. So for the average person, it’s probably a good idea to educate yourself and understand your personal threat model. In business, when you are the stakeholder for the assets of your business, it means hiring people with the resume that you don’t to be a good CISO or some other type of security advocate.

Another way to look at it is to compare this to having a lawyer. If you hire a lawyer, whether it’s as a company or personally, they don’t just start “lawyering”. You must give them direction about what their mission is. You, the stakeholder, has to synthesize that. If you don’t understand security in a similar way to know which of your assets is more valuable, that’s just something you’ve got to learn.

BS: It seems like the stakeholder is paying for this stuff one way or another. Either they are paying for incomplete or inefficient security by relying on their provider to be wholly responsible, or they are ignoring it and just hoping for the best. It’s a race to the bottom.

SB: Security is a completely misunderstood feature when it’s being sold, and it’s unbelievably oversold and inflated. Everything says “secure” on it… it’s on every box you ever buy. But is it really “secure”? What does that even mean?

This applies to the consumer, businesses, government, etc. People sell things that have “military grade encryption” and other buzzwordy terms. It’s very easy to make these claims and still be inherently insecure. You shouldn’t read a bullet list description of security things and then assume it’s good. It generally doesn’t tell you much of anything. Self-attestation is not really acceptable for real security.

A long time ago, there was this idea people believed that Macs were more secure than Windows machines, but everybody knew the big part of this, at the time, was that there were simply fewer in use. The market share was insanely different 20 years ago. Why would criminals go after the 10% or so of the market when there’s this whole other side of things to hack that are more lucrative? Well, after time, as market shares adjusted, it was clear that Macs weren’t quite as strong security-wise as they made it out to be.

That’s something about security that is not as easy to grasp. Stakeholders don’t know what to do about it and providers generally lack the knowledge to adequately provide solutions to. All of these security solutions, from encryption, to 2FA, to any other kind of security feature…until we look at how these tools are built and look for vulnerabilities, we don’t really know if it’s secure. Security is both micro and macro. Having good security tools in place but having validation to make sure things are done in the right way.

BS: Do you think providers are expected to know more about security and that’s why many people associate them with responsibility for it?

SB: I certainly don’t think the provider knows the most about security. Most people think that, but it says a lot that people think it. The providers mean well and do what they think is right.

But security is conflated with technology constantly. In fact, people who are in charge of managing security often end up reporting to the CIO or CTO. But the security responsibility should be separate from the technology management and implementation responsibilities. The expertise is just different. You can probably see why this is a problem for having providers responsible. Unless they are a security provider specifically, they probably lack the expertise.

Just because you are a “tech guy” doesn’t mean you know more about security than someone else, and vice versa. Although, you’re probably in good shape career-wise if you happen to know both these days.

BS: As more connected devices, applications, and technology in general exist in our daily lives, do you think stakeholders, whether they like it or not, will be compelled to be more responsible for their own security?

SB: I think maybe a better way to look at the problem would be who can and can’t do something about it. If the stakeholder has no resources, they aren’t going to be able to do anything about it no matter what. If the stakeholder has more resources than the provider, then they must do more. I wouldn’t expect a company buying a product from, say, Microsoft, to do a security assessment of their product. They are the small fish and Microsoft is the big fish.

But if you flip that around and you are Microsoft, and you are purchasing some kind of equipment or software from a smaller organization (which is probably inevitable for most Microsoft vendors), your losses are going to be much higher if that product you are buying is insecure and compromised. You better make the investment in security, because you shouldn’t expect your vendor to.

One way to look at it is to examine the incentive structure itself, like I just did with my example. If the incentive structure of the system for security is bad, it can be a vulnerability in and of itself. If the little guy is fully responsible for the security of the big guy, that incentive structure doesn’t make sense. The little guy won’t lose the hundreds of millions of dollars that the enterprise loses. They will only be able to commit what the business with the enterprise they are working with is worth. In industries where you have high value assets, you need to be considering what stake your providers actually have. If it’s low, you probably want to do more.

BS: Steve, thanks so much for chatting with me about this. It’s very insightful. Any final thoughts?

SB: The thing that made this click with me was when I started working with big companies with extremely valuable assets, particularly in the movie industry. These studios produce films that are worth hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars. This requires the effort not only of the studios, but vendors down the line, many of which are far smaller. Often the entire operating budgets of these vendors are probably a tiny fraction of what these studios spend on one project. But these studios were willing to make huge investments in security that many times were more significant than the price of just doing business with their vendors. Why? Because the studios know these films were assets worth protecting. They must make the investment because they know their provider can’t. They are the stakeholder. They take the responsibility.

Want to learn more about how to better control the security of your assets? Contact us today!

[1] If you want to learn more about practical threat modeling, check out this blog about effective threat modeling: https://blog.securityevaluators.com/a-hackers-perspective-on-faulty-threat-models-for-blockchain-assets-aeb193360274